This is the fifteenth entry in an ongoing monthly (or almost monthly!) series profiling the amazing identifiers of iNaturalist.

Lichens! These symbiotic organisms occur all over the place but are often overlooked by many people. However, to Jurga Motiejūnaitė, iNat’s top identifier of common lichens,

there are many exciting things about lichens: they are very colourful, they grow practically anywhere, some (like Ramalina menziesii [California’s state lichen! - Tony], or Pulchrocladia, or Stellarangia, or Eremastrella) have really crazy forms. Another pleasant thing is that they are not seasonal - one can find and enjoy them all year round (unless they are under deep snow cover). Some are very long lived and one can visit the same thallus for a number of years (if the habitat does not change dramatically). And even more interesting, lichens have parasites - lichenicolous fungi, which are spectacular by themselves.

Jurga lives in Lithuania and works at the Mycology Laboratory at the Nature Research Centre in Vilnius, where she studies lichens and lichenicolous fungi. She remembers catching pond organisms as a child, and collecting and identifying mushrooms and herbs with her parents and grandparents. When attending university, she studied plant communities and, after getting a job at the Botanical Institute, she started researching lichens.

When identifying on iNaturalist, Jurga often starts out by filtering for fungi, Lecanoromycetes, or other taxa, and “for identification I use either personal knowledge, or consult extensive lichen literature that I own. For quick checks, especially for morphological variations of lichens, I use several reliable internet resources (e.g. ITALIC, Lichenportal, Lichens marins, etc.). Regretfully, online resources tend to disappear, change addresses and create inconveniences, so recommending them to other users is difficult…

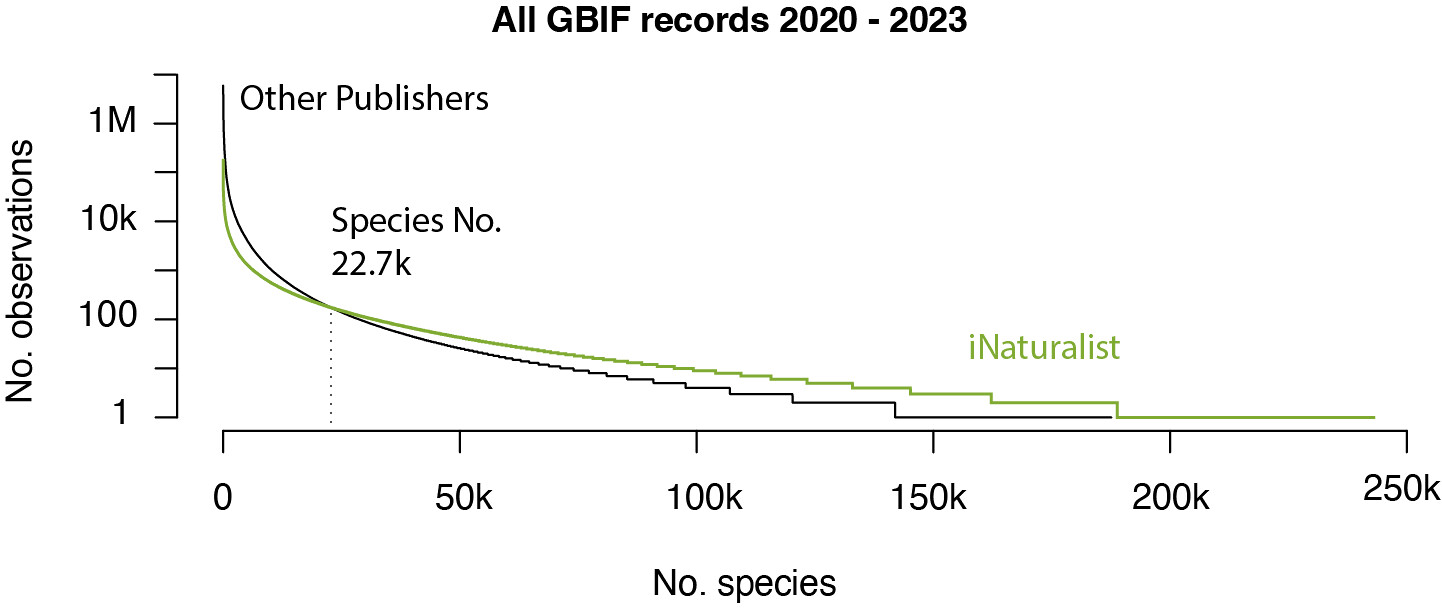

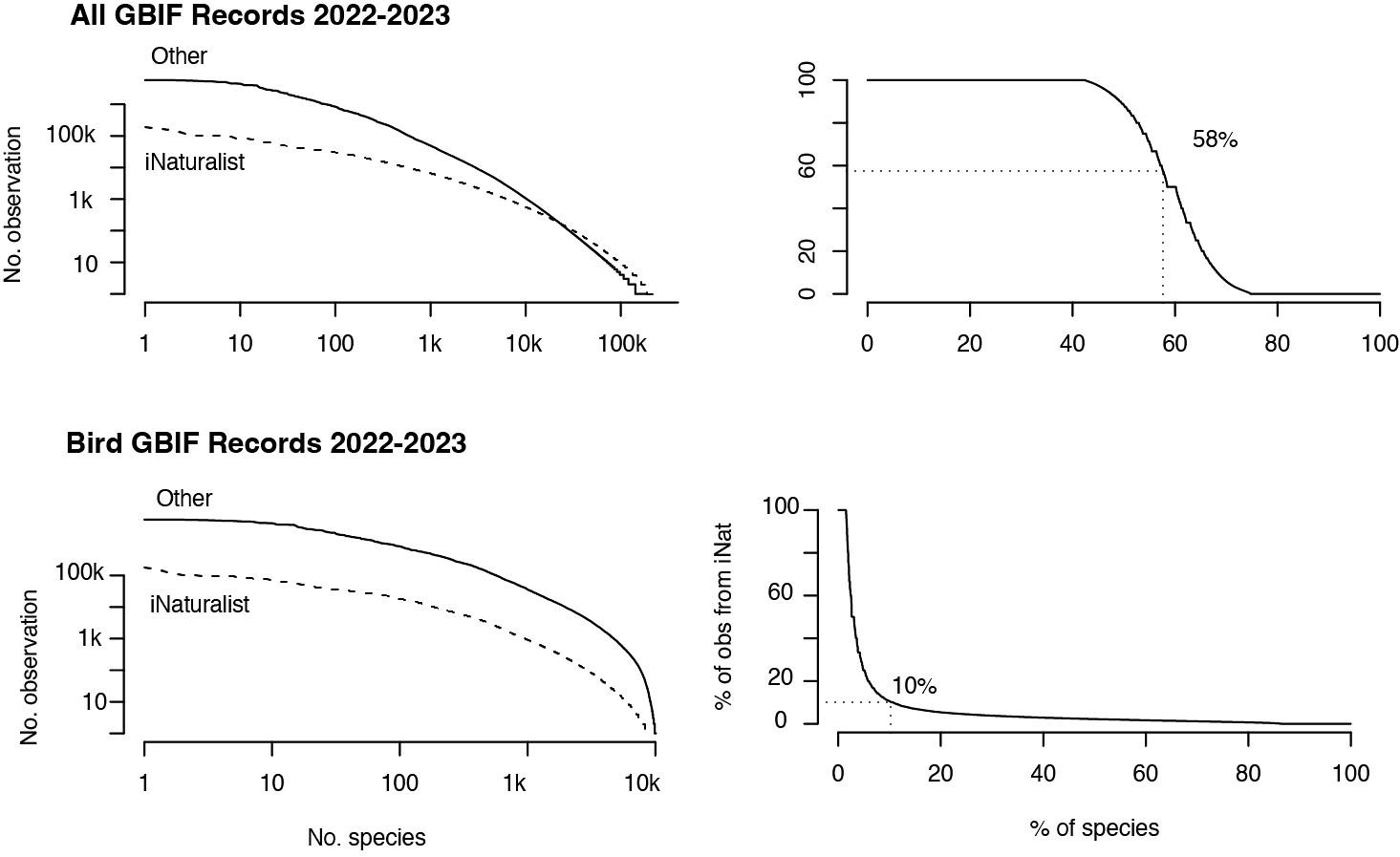

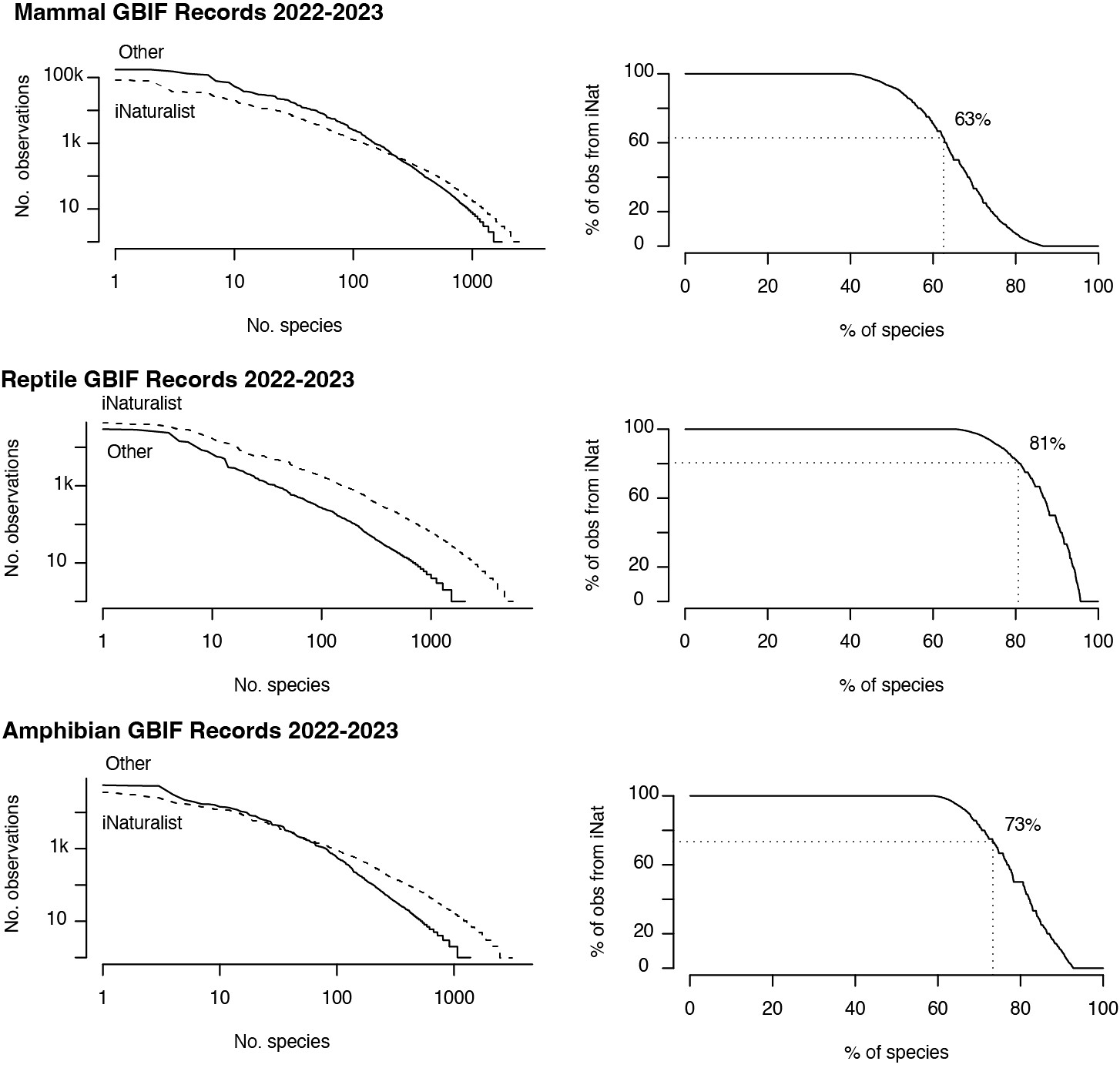

Identification is part of my job, and identification from photographs gives me a different skill set from that required for specimen identification. As with any researcher, I like things to be as correct as possible, especially because Research Grade observations go to GBIF. I respect cleanliness of the data. I do not add comments to all observations. Many users seem to not be very interested, but when people ask questions, I always respond. I am particularly pleased when iNaturalist users take an interest in lichens and make obvious progress in their knowledge.

While Jurga’s focus is mostly on lichen and fungi in northern Europe, she’s helped out with identifications in southern Africa “because previously there was no one identifying lichens there, and I had gathered some identification material. But now I can almost resign from that position, because @ian_medeiros has taken over, and he is working directly on the lichenoflora of that region. I am very happy about this, as well as the fact that more lichenologist colleagues have joined iNaturalist.”

Introduced to iNat by Almantas Kulbis (@almantas), “a passionate promoter of iNaturalist in Lithuania, who works in non-formal education for students,” she says, Jurga joined in 2018. “By the way, it is especially thanks to him and his colleagues that iNaturalist is so popular in Lithuania.”

I use iNaturalist myself for many reasons. First and foremost, for entertainment and self-education. It is a wonderful tool to keep the mind and body (after all, you need to walk a lot!) active. It's also great fun to go back to my early experiences of trying to learn about different organisms in nature, not just the ones I study. Another area is education. I also encourage people to get involved in these activities when they have the opportunity - to look back at nature, to see its extraordinary diversity, to start respecting it more.

And finally, I use iNaturalist for work. Mycologists in Lithuania are few and far between, so citizen science is very useful for collecting the data on distribution of fungi and lichen species. Thanks to the iNaturalist community alone, one species that had not been found in Lithuania before and one that was thought to be extinct were found. Of course, IDing lichens from photos (even very good ones) is problematic, as most of them require microscopy or chemical tests (or at least reagent reactions and UV light). But it is still possible to ID some of them, so the iNaturalist community should not stop uploading observations of lichens, even if they can sometimes only be IDed down to the class level.

(Some quotes have been lightly edited for clarity.)

- Speaking of southern Africa, here’s an undescribed lichen from that region that Jurga helped get identified. Great discussion!

- When it comes to lichens, “Ramalina menziesii or genera Niebla and Pulchrocladia are my absolute favourites,” says Jurga.

- And finally, some adivce for finding and phtoographing lichens. “Lichens can indeed be found almost anywhere: even in water on the half or fully submerged rocks or on shells of barnacles. The only problem is that for many lichens a hand lens is required even to find them and a very good macro lens is needed to take a photo. For these which can be seen by the naked eye, my advice is to take several photos: one of general view of the thallus, one close up of any structures present on the thallus (ascomata, vegetative propagules, pseudocyphellae, etc.) and one close up of the edge of the thallus. For some foliose lichens (Peltigera, Nephroma, some others) view of both sides of thallus is obligatory.”

- Check out the Lichenicolous Fungi of the World project!