Our Observation of the Week is this Nevada Oryctes (Oryctes nevadensis), seen in the United States by @swinitsky!

As a child growing up in Los Angeles, Sophie Witnisky says she didn’t encounter much real wilderness but learning to garden “helped me develop an eye for biodiversity and I wanted to learn as much as I could, specifically about plants.” After some time working in sustainable agriculture, she heard about professional botanists

and that shifted everything. My first solo and careful exploration of wilderness came when I took a seasonal job (living right next to where we found the Oryctes nevadensis!) with the Inyo National Forest. From there, my life has been shaped by searching for, identifying and asking questions to plants.

Currently a student at Montana State University, she studies Marina, “a mostly Mexican, glandular, arid-dwelling genus of legume.” Another area of interest is the flora of the Eastern Sierra, “specifically areas impacted by the LA aqueduct.”

[Growing up in Los Angeles,] I felt a personal connection and responsibility towards the land and water grab between eastern California and Los Angeles. It felt right to pursue research that follows up on the long term botanical impacts of the aqueduct. This week I published a conservation plan [PDF] for Calochortus excavatus, a rare plant that runs the entire length of the aqueduct and my M.S. research was on the flora of alkali meadows and marshes, the habitat most impacted by the aqueduct. I also follow this entire area on iNaturalist, which allows me to plan my fieldwork efficiently, since phenology fluctuates a lot, and to keep an eye out for plants I don't know.

In May of 2019, Sophie was in the area with three other botanists: Isaac Marck (@california_naturalist), Maria Jesus (@mariaj),j and Nico Medina (@botanico_las), “which makes looking for plants a lot more fun and a lot slower paced.”

The Oryctes nevadensis population we documented is along the Owens River, which is severely impacted by the aqueduct. This area is heavily botanized - it's California! - so finding something so rare, close to highway 395, reminds us how much there is to learn. The other known populations are farther south and are quite likely extirpated, they were last documented in the early 1980s. We had heard about this population found on sand dunes near the White Mountain Research Station, in Bishop, where we were staying, but the plants rarely come up since they need a specific precipitation regime.

Expectations were low since we heard this population was last seen in the fifties, but it was so snowy (even though it was summer, note the strange rain pattern) that our more glamorous botanizing locations were inaccessible...This population is also highly at risk due to the off roading that happens directly on the plants. They don't look like rare wildflowers, they look like sticky weeds, or perhaps even escaped tomatoes!

The nondescript appearance of Oryctes nevadensis is also a plus for Jim Morefield (@jdmore), a botanist with the Nevada Division of Natural Heritage, who was kind enough to tell me a bit more about the species. “As an inconspicuous desert annual,” he says, “Oryctes nevadensis is automatically on my list of favorite plants.” However, he’s never actually come across one.

Seeing Oryctes nevadensis in the flesh has been on my bucket list for the entire 30 years I have worked as a rare plant botanist in Nevada, but the timing just never worked out. So imagine my delight (and sense of irony) at seeing the first live photos of the species in Sophie’s well-documented observation from California! Its main geographic range is in the sandy valleys of the Lahontan Basin in west-central Nevada, and it only barely spills over into California in similar habitats at the southwestern corner of its range. It is found nowhere else in the world.

The species was first discovered and named in 1871, from specimens found near the lower Truckee River. This rare desert annual is of conservation concern in both Nevada and California, and it is so rarely seen because of its inconspicuous appearance and tendency to germinate only in exceptionally wet spring seasons, like 2019 was.

Due to its rarity, Jim tells me little else is known about the species, although it does belong to the nightshade family (Solanaceae), hence its similarity to tomatoes.

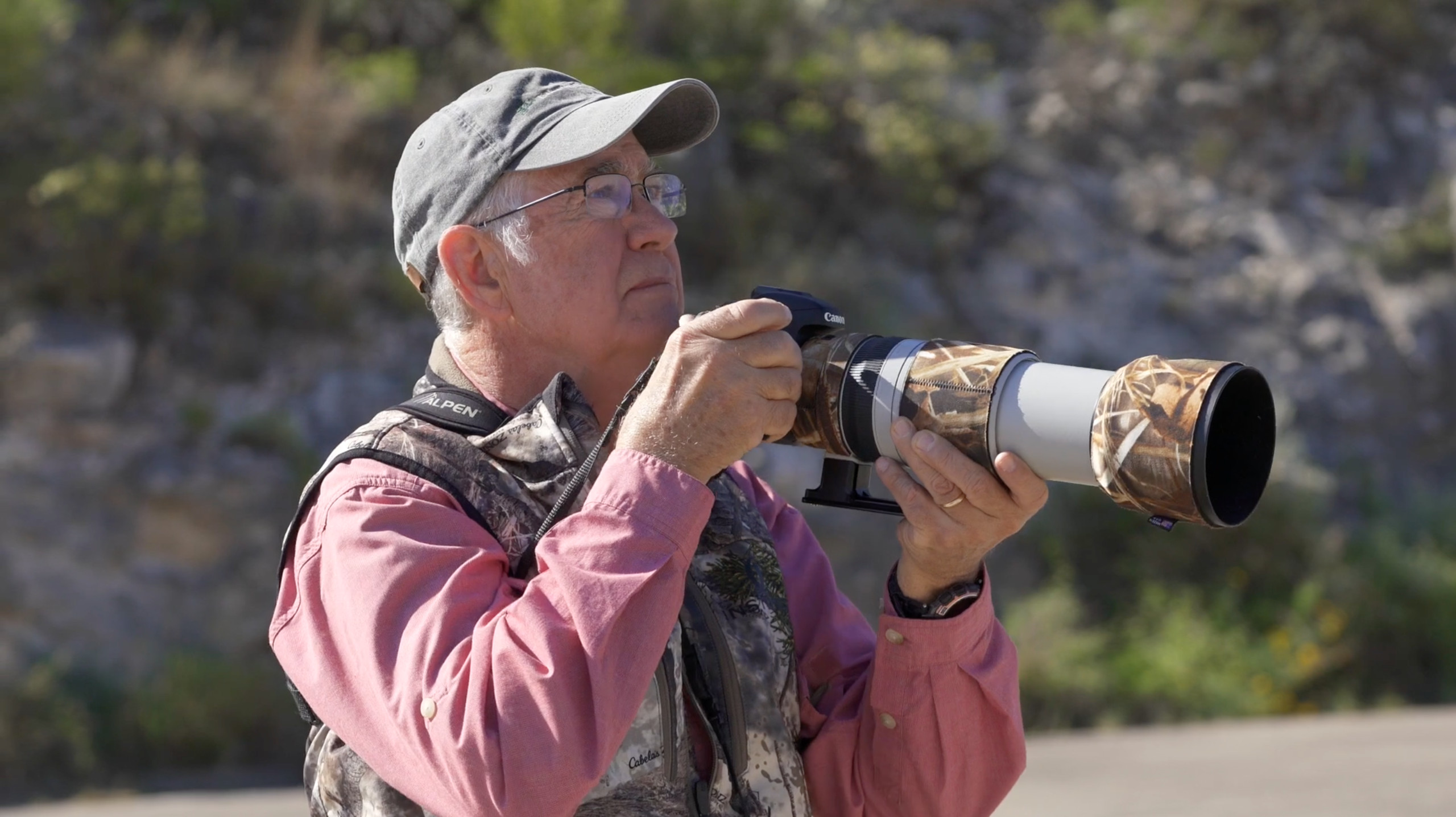

In addition to posting photos of rare plants, Sophie (above) uses iNat in her research on Marina. “Many of these beans have only been seen a couple times or are just known from type collections, so iNaturalist is incredibly helpful,” she explains.

Like Oryctes, they can look weedy or uninteresting (obviously I do not agree) and can be easily overlooked, but uploading them to iNat is easy and advances our understanding of their distribution. I am working on the systematics of the group as a PhD project and hoping to better understand their rarity, evolution, biogeography and conservation. I follow them and all their close relatives on iNaturalist and it helps me track phenology, plan my fieldwork and network with local botanists.

(Photo of Sophie by Isaac Marck)

- You can take a look at Sophie’s website here, and her Instagram feed here!